nLab sphere

Context

Spheres

Topology

topology (point-set topology, point-free topology)

see also differential topology, algebraic topology, functional analysis and topological homotopy theory

Basic concepts

-

fiber space, space attachment

Extra stuff, structure, properties

-

Kolmogorov space, Hausdorff space, regular space, normal space

-

sequentially compact, countably compact, locally compact, sigma-compact, paracompact, countably paracompact, strongly compact

Examples

Basic statements

-

closed subspaces of compact Hausdorff spaces are equivalently compact subspaces

-

open subspaces of compact Hausdorff spaces are locally compact

-

compact spaces equivalently have converging subnet of every net

-

continuous metric space valued function on compact metric space is uniformly continuous

-

paracompact Hausdorff spaces equivalently admit subordinate partitions of unity

-

injective proper maps to locally compact spaces are equivalently the closed embeddings

-

locally compact and second-countable spaces are sigma-compact

Theorems

Analysis Theorems

Manifolds and cobordisms

manifolds and cobordisms

cobordism theory, Introduction

Definitions

Genera and invariants

Classification

Theorems

Contents

Definition

Finite-dimensional spheres

Definition

The -dimensional unit sphere , or simply -sphere, is the topological space given by the subset of the -dimensional Cartesian space consisting of all points whose distance from the origin is

The -dimensional sphere of radius is

Topologically, this is equivalent (homeomorphic) to the unit sphere for , or a point for .

This is naturally a smooth manifold of dimension , with the smooth structure induced by the standard smooth structure on .

Infinite dimensional spheres

One can also talk about the infinite-dimensional sphere in an arbitrary (possibly infinite-dimensional) normed vector space :

If a locally convex topological vector space admits a continuous linear injection into a normed vector space, this can be used to define its sphere. If not, one can still define the sphere as a quotient of the space of non-zero vectors under the scalar action of .

Homotopy theorists (e.g. tom Dieck 2008, example 8.3.7) define as the directed colimit of the :

Note that this is not homeomorphic to the sphere of any metrizable space as defined above, since the metrizable CW-complexes are precisely the locally finite CW-complexes (Fritsch–Piccinini 1990: 48, prop. 1.5.17), which is not (every open -cell intersects all closed -cells with )

In themselves, infinite-dimensional spheres provide nothing new to homotopy theory, as they are at least weakly contractible and usually contractible. However, they are a very useful source of big contractible spaces and so are often used as a starting point for making concrete models of classifying spaces.

If the vector space is a shift space, then contractibility is straightforward to prove.

Theorem

Let be a shift space of some order. Let be its sphere (either via a norm or as the quotient of non-zero vectors). Then is contractible.

Proof

Let be a shift map. The idea is to homotop the sphere onto the image of , and then down to a point.

It is simplest to start with the non-zero vectors, . As is injective, it restricts to a map from this space to itself which commutes with the scalar action of . Define a homotopy by . It is clear that, assuming it is well-defined, it is a homotopy from the identity to . To see that it is well-defined, we need to show that is never zero. The only place where it could be zero would be on an eigenvector of , but as is a shift map then it has none.

As is a shift map, it is not surjective and so we can pick some not in its image. Then we define a homotopy by . As is not in the image of , this is well-defined on . Combining these two homotopies results in the desired contraction of .

If admits a suitable function defining a spherical subset (such as a norm) then we can modify the above to a contraction of the spherical subset simply by dividing out by this function. If not, as the homotopies above all commute with the scalar action of , they descend to the definition of the sphere as the quotient of .

Properties

Basic

-

These spheres, or rather their underlying topological spaces or simplicial sets, are fundamental in (ungeneralised) homotopy theory. In a sense, Whitehead's theorem says that these are all that you need; no further generalised homotopy theory (in a sense dual to Eilenberg–Steenrod cohomology theory) is needed.

-

positive dimension spheres are H-cogroup objects, and this is the origin of the group structure on homotopy groups).

This proposition can be generalized:

A special case of this proposition is for the topological complexity of the torus.

CW-structures

The -sphere is an -dimensional CW complex in several ways:

-

The -sphere () admits, for every point , a CW-structure with one -cell and one -cell , by stereographic projection. (tom Dieck 2008, example 8.3.7)

-

The -sphere () can also be constructed from the -sphere by attaching -cells (the north and south hemispheres) to the equator -sphere. Iteratively applying this construction starting with yields a CW complex with two -cells in each dimension , and subcomplex inclusions for all ; the colimit of this sequence is (by definition) . (tom Dieck 2008, example 8.3.7)

Coset space structure

As quotients of compact Lie groups

Proposition

For the n-spheres are coset spaces of orthogonal groups

Similarly for the corresponding special orthogonal groups

and spin groups

and pin groups

Proof

Fix a unit vector in . Then its orbit under the defining -action on is clearly the canonical embedding . But precisely the subgroup of that consists of rotations around the axis formed by that unit vector stabilizes it, and that subgroup is isomorphic to , hence .

Similarly, the analogous argument for unit spheres inside (the real vector spaces underlying) complex vector spaces, we have

Proposition

For the (2k+1)-sphere is the coset space of special unitary groups:

And still similarly, the analogous argument for unit spheres inside (the real vector spaces underlying) quaternionic vector spaces, we have

Proposition

For , the (4k-1)-sphere is the coset space of quaternionic unitary groups:

Generally:

Proposition

The connected compact Lie groups with effective transitive actions on n-spheres are precisely (up to isomorphism) the following:

with coset spaces

This goes back to Montgomery & Samelson (1943), see Gray & Green (1970), p. 1-2, also Borel & Serre (1953), 17.1.

Remark

The isomorphisms in Prop. and Prop. above hold in the category of topological spaces (homeomorphisms), but in fact also in the category of smooth manifolds (diffeomorphisms) and even in the category of Riemannian manifolds (isometries).

The other coset space realizations of some n-spheres in Prop. are homeomorphisms, but not necessarily isometries (“squashed spheres”). There is also a double coset space realization which is not even a diffeomorphisms (“exotic sphere”, the Gromoll-Meyer sphere).

For more see 7-sphere – Coset space realization.

coset space-structures on n-spheres:

| standard: | |

|---|---|

| this Prop. | |

| this Prop. | |

| this Prop. | |

| exceptional: | |

| Spin(7)/G2 is the 7-sphere | |

| since Spin(6) SU(4) | |

| since Sp(2) is Spin(5) and Sp(1) is SU(2), see Spin(5)/SU(2) is the 7-sphere | |

| G2/SU(3) is the 6-sphere | |

| Spin(9)/Spin(7) is the 15-sphere |

see also Spin(8)-subgroups and reductions

homotopy fibers of homotopy pullbacks of classifying spaces:

(from FSS 19, 3.4)

As quotients of Lorentz groups

If one drops the assumption of compactness, then there are further coset space realizations of -spheres, notably as quotients of Lorentz groups by parabolic subgroups: celestial spheres, e.g.: Toller (2003, p. 18), Varlamov (2006, p. 6), Math.SE:a/4092474.

Spin structure

Example

The -sphere, for each , carries a canonical spin structure, induced from its coset space-realization (above), as a special case of the canonical -structure on (this example).

Other ways to see this:

-

Nikolai Nowaczyk, Theorem A.6.6 in: Dirac Eigenvalues of higher Multiplicity, Regensburg 2015 (arXiv:1501.04045)

-

S. Gutt, Killing spinors on spheres and projective spaces, p. 238-248 in: A. Trautman, G. Furlan (eds.) Spinors in Geometry and Physics – Trieste 11-13 September 1986, World Scientific 1988 (doi:10.1142/9789814541510, GBooks, p. 243)

Parallelizability

-

Precisely four spheres are parallelizable, and three of these are so via Lie group structure (hence are the only spheres with Lie group structure) (see at Hopf invariant one theorem):

-

(the group of order two, the group of units of the real numbers);

-

(the circle group, the group of unit complex numbers);

-

(the special unitary group , the group of unit quaternions);

-

(the Moufang loop of unit octonions)

-

Branched covers

Every -dimensional PL manifold admits a branched covering of the n-sphere (Alexander 20).

By the Riemann existence theorem, every connected compact Riemann surface admits the structure of a branched cover by a holomorphic function to the Riemann sphere. See there at branched cover of the Riemann sphere.

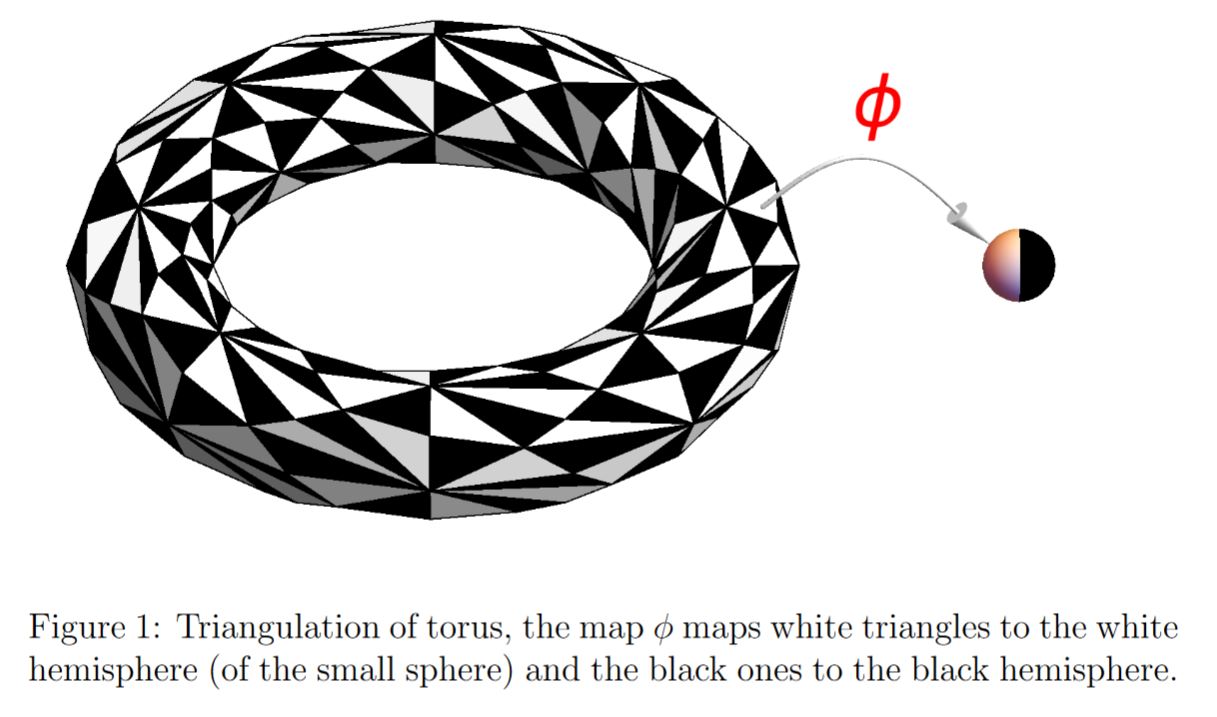

graphics grabbed from Chamseddine-Connes-Mukhanov 14, Figure 1, Connes 17, Figure 11

For 3-manifolds branched covering the 3-sphere see (Montesinos 74).

All PL 4-manifolds are simple branched covers of the 4-sphere (Piergallini 95, Iori-Piergallini 02).

But the n-torus for is not a cyclic branched over of the n-sphere (Hirsch-Neumann 75)

Iterated loop spaces

Proposition

(rational cohomology of iterated loop space of the 2k-sphere)

Let

(hence two positive natural numbers, one of them required to be even and the other required to be smaller than the first) and consider the D-fold loop space of the n-sphere.

Its rational cohomology ring is the free graded-commutative algebra over on one generator of degree and one generator of degree :

(Kallel-Sjerve 99, Prop. 4.10)

Examples

-

The -sphere is the empty space.

-

The 0-sphere is the disjoint union of two points (the classical boolean domain).

-

The 2-sphere is usual sphere from ordinary geometry. This canonically carries the structure of a complex manifold which makes it the Riemann sphere.

-

The 3-sphere and 4-sphere, 5-sphere and 6-sphere and 7-sphere are interesting, too.

Related concepts

-

The non-abelian generalized cohomology theory represented by n-spheres is Cohomotopy cohomology theory.

References

-

Rudolf Fritsch, Renzo A. Piccinini, Cellular structures in topology, Cambridge studies in advanced mathematics Vol. 19, Cambridge University Press (1990). (doi:10.1017/CBO9780511983948)

-

Tammo tom Dieck, Algebraic topology. European Mathematical Society, Zürich (2008) (doi:10.4171/048)

Formalization

Axiomatization of the homotopy type of the 1-sphere (the circle) and the 2-sphere, as higher inductive types, is in

- Univalent Foundations Project, section 6.4 of Homotopy Type Theory – Univalent Foundations of Mathematics

Visualization of the idea of the construction for the 2-sphere is in

- Andrej Bauer, HoTT (video)

Group actions on spheres

Discussion of free group actions on spheres by finite groups includes

-

C. T. C. Wall, Free actions of finite groups on spheres, Proceedings of Symposia in Pure Mathematics, Volume 32, 1978 (pdf)

-

Alejandro Adem, Constructing and deconstructing group actions (arXiv:0212280)

The subgroups of SO(8) which act freely on have been classified in

- J. A. Wolf, Spaces of constant curvature, Publish or Perish, Boston, Third ed., 1974

and lifted to actions of Spin(8) in

- Sunil Gadhia, Supersymmetric quotients of M-theory and supergravity backgrounds, PhD thesis, School of Mathematics, University of Edinburgh, 2007 (spire:1393845)

Discussion of transitive actions on -spheres by compact Lie groups:

-

Deane Montgomery, Hans Samelson, Transformation Groups of Spheres, Annals of Mathematics Second Series 44 3 (1943) 454-470 [jstor:1968975]

-

Alfred Gray, Paul S. Green, Sphere transitive structures and the triality automorphism, Pacific J. Math. Volume 34, Number 1 (1970), 83-96 (euclid:1102976640)

Further discussion of these actions is in

-

Paul de Medeiros, José Figueroa-O'Farrill, Sunil Gadhia, Elena Méndez-Escobar, Half-BPS quotients in M-theory: ADE with a twist, JHEP 0910:038,2009 (arXiv:0909.0163, pdf slides)

-

Paul de Medeiros, José Figueroa-O'Farrill, Half-BPS M2-brane orbifolds, Adv. Theor. Math. Phys. Volume 16, Number 5 (2012), 1349-1408. (arXiv:1007.4761, Euclid)

where they are related to the black M2-brane BPS-solutions of 11-dimensional supergravity at ADE-singularities.

See also the ADE classification of such actions on the 7-sphere (as discussed there)

Discussion of actions of Lorentz groups on celestial spheres:

-

Marco Toller, Homogeneous Spaces of the Lorentz Group [arXiv:math-ph/0301014]

-

V. V. Varlamov, Relativistic Spherical Functions on the Lorentz Group, J. Phys. A: Math. Gen. 39 (2006) 805-822 [doi:10.1088/0305-4470/39/4/006]

Geometric structures on spheres

Coset space structures on spheres:

- Armand Borel, Jean-Pierre Serre, Groupes de Lie et Puissances Reduites de Steenrod, American Journal of Mathematics, Vol. 75, No. 3 (Jul., 1953), pp. 409-448 (jstor:2372495)

The following to be handled with care:

- Michael Atiyah, The non-existent complex 6-sphere, arxiv/1610.09366

Embeddings of spheres

The (isotopy class of an) embedding of a circle (1-sphere) into the 3-sphere is a knot. Discussion of embeddings of spheres of more general dimensions into each other:

- André Haefliger, Differentiable Embeddings of in for , Annals of Mathematics Second Series, Vol. 83, No. 3 (May, 1966), pp. 402-436 (jstor:1970475)

Iterated loop spaces

- Sadok Kallel, Denis Sjerve, On Brace Products and the Structure of Fibrations with Section, 1999 (pdf, pdf)

Topological complexity

On topological complexity of spheres and products of spheres (including tori as special case):

- Michael Farber, Topological complexity of motion planning (2001), arXiv:math/0111197;

Last revised on February 14, 2024 at 06:37:01. See the history of this page for a list of all contributions to it.