nLab chord diagram

This entry is about standard round chord diagrams. For linear chord diagrams or horizontal chord diagrams or Jacobi diagrams or Sullivan chord diagrams see there.

Context

Combinatorics

Basic structures

- binary linear code

- chord diagram

- combinatorial design

- graph

- Latin square

- matroid

- partition

- permutation

- shuffle

- tree

- Young diagram

Generating functions

Proof techniques

Combinatorial identities

Polytopes

Knot theory

Examples/classes:

Types

Related concepts:

Contents

Idea

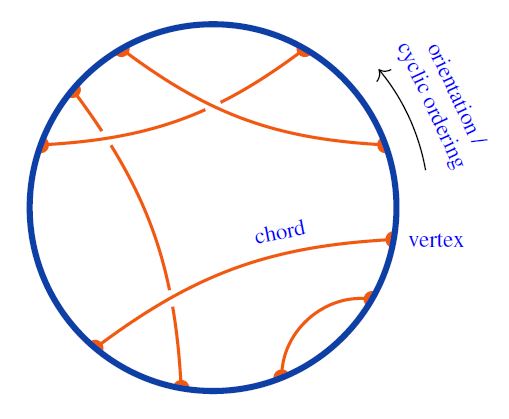

A chord diagram is a finite trivalent undirected graph with an embedded oriented circle and all vertices on that circle, regarded modulo cyclic identifications, if any.

A typical chord diagram looks like this:

graphics from Sati-Schreiber 19c

Equivalently this is a pairing (by chords) of all elements in a cyclic order (the boundary vertices).

Chord diagrams are a basic object of study in combinatorics with remarkably many applications in mathematics and physics, notably in knot theory and Chern-Simons theory (where they control Vassiliev invariants) but more recently also in stringy quantum gravity (see the references below).

If also (trivalent) internal vertices are considered, one speaks of Jacobi diagrams. Under standard equivalence relations these are actually equivalent to chord diagrams, see below).

Definitions

Chord diagrams can be defined both in topological terms, which formalize the graphical intuition, as well as in purely combinatorial terms. We present only the combinatorial definition here, starting from rooted chord diagrams and using those to define unrooted chord diagrams, rather than the other way around.

(For topological definitions of both unrooted and rooted chord diagrams, see for example Chapter 6 of Lando and Zvonkin, or Definition 1.5 of Bar-Natan 1995 for the unrooted case.)

A combinatorial definition

Rooted chord diagrams

If we would label the points of a chord diagram,

then the chords can be seen as describing a matching (or equivalently, an involution) on the set of marked points which pairs (or equivalently, swaps) with , with , and with .

A subtle point is that a chord diagram can have non-trivial symmetries when considered up to this action of rotation. For that reason, in many situations it is useful to equip the circle with a distinguished basepoint (distinct from the marked points), the result being called a rooted chord diagram. Rooted chord diagrams may be conveniently visualized by “cutting open” the circle at the basepoint. For example, here we have rooted the chord diagram above at a basepoint lying on the interval AF, and opened up the circle:

The marked points of a rooted chord diagram are intrinsically equipped with a linear order () rather than a cyclic order.

Finally, it is also at times useful to consider chord diagrams with marked points which are not attached to any chord; if we think of the diagram as representing an involution, then this allows for the possibility of representing involutions with fixed points.

Definition

A rooted chord diagram of order is a surjective monotone function

from the -fold coproduct of the walking arrow (seen as a 2-element poset) into the linear order . The symmetric group acts freely on the domain of a rooted chord diagram of order , and we consider two rooted chord diagrams to be isomorphic if they only differ by precomposition with such a permutation action.

Equivalently, a rooted chord diagram of order is a way of arranging the elements of into a collection of (necessarily mutually disjoint) ordered pairs , where for each .

Equivalently, a rooted chord diagram of order is a shuffle of distinct 2-letter words , , , etc., considered up to alpha-conversion. Under this view, rooted chord diagrams are also sometimes referred to as double-occurrence words. (For example, the rooted chord diagram in the illustration above can be encoded as the double-occurrence word .)

Unrooted chord diagrams

Intuitively, the cyclic group acts on rooted chord diagrams

by acting on the codomain via the map . This is not quite well-typed, however, since the composite function is not quite order-preserving. It is easiest to define the action of in terms of the view of a rooted chord diagram as a collection of ordered pairs . The action of is defined on each pair by

and this extends to an action on rooted chord diagrams by acting independently on the pairs.

Definition

An unrooted chord diagram of order is a rooted chord diagram of order , considered up to the action of .

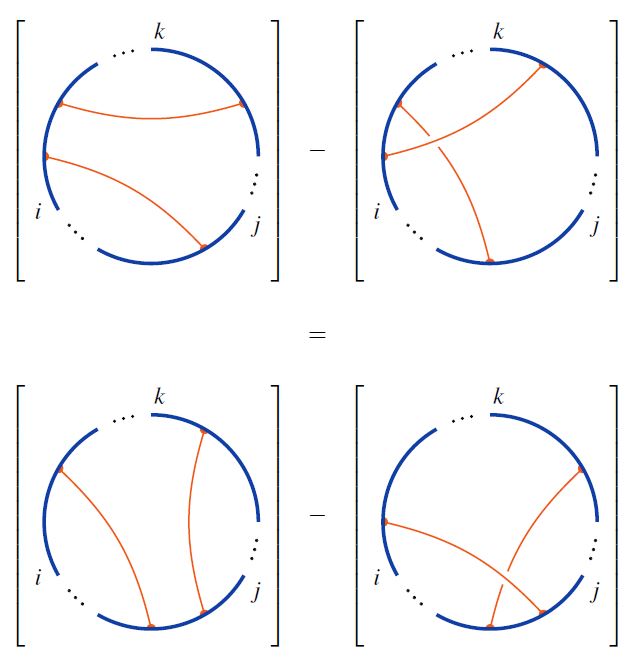

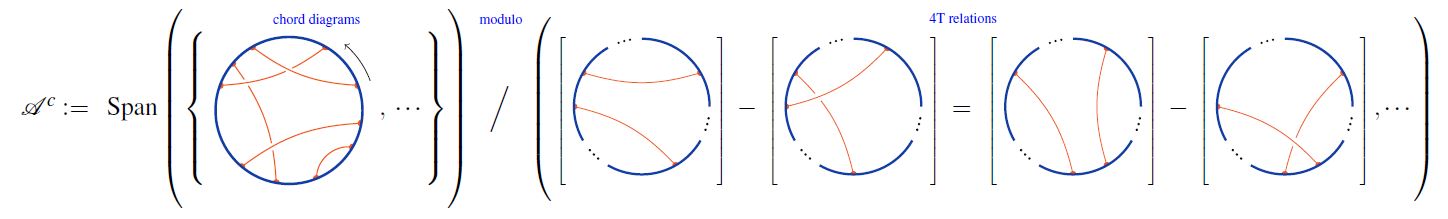

4T relation and weight systems

Often one is interested in chord diagrams only modulo the 4T relation:

For CRing a commutative ring, let denote the -linear span of the set of chord diagrams.

Then one traditionally writes

for the quotient spaces of the linear span of chord diagrams by the 4T relations:

Hence:

graphics from Sati-Schreiber 19c

– hence a plain -valued function on the set of chord diagrams which is invariant under the 4T relation –

is called a framed weight system. See there for more.

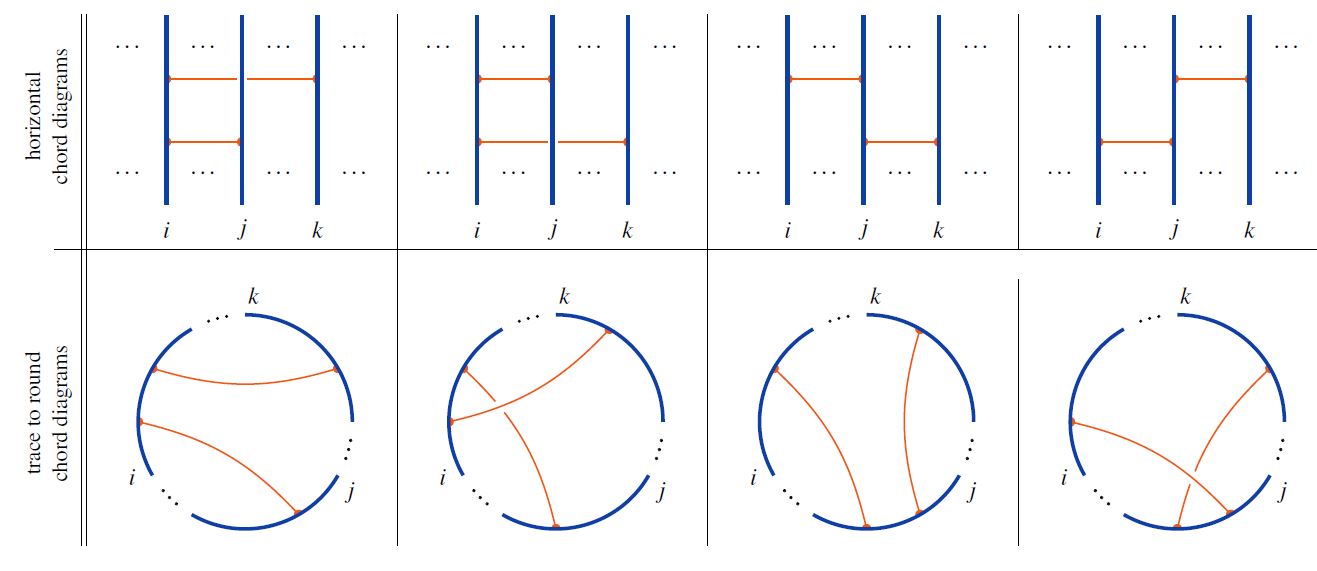

Trace from horizontal chord diagrams

Given a horizontal chord diagram on strands and given any choice of cyclic permutation of elements, the trace of horizontal to round chord diagrams is the round chord diagram obtained by gluing the ends of the strands according to the cyclic permutation, and retaining the chords in the evident way.

The following graphics shows basic examples of the trace operation for cyclic permutation of strands one step to the right:

graphics from Sati-Schreiber 19c

This defines a function

from the set of horizontal chord diagrams to the set of round chord diagrams.

Properties

Representation as involutions

Every rooted chord diagram

uniquely determines a fixed point free involution

swapping the elements of each chord,

and conversely, any such involution uniquely determines a rooted chord diagram up to isomorphism. In particular, there are a double-factorial number

of distinct isomorphism classes of rooted chord diagrams of order .

Symmetries

Every rooted chord diagram uniquely determines a chord diagram simply by forgetting the basepoint. Conversely, an unrooted chord diagram of order can be rooted in up to different ways (corresponding to the intervals between the marked points), but might also have fewer rootings in the case of symmetries.

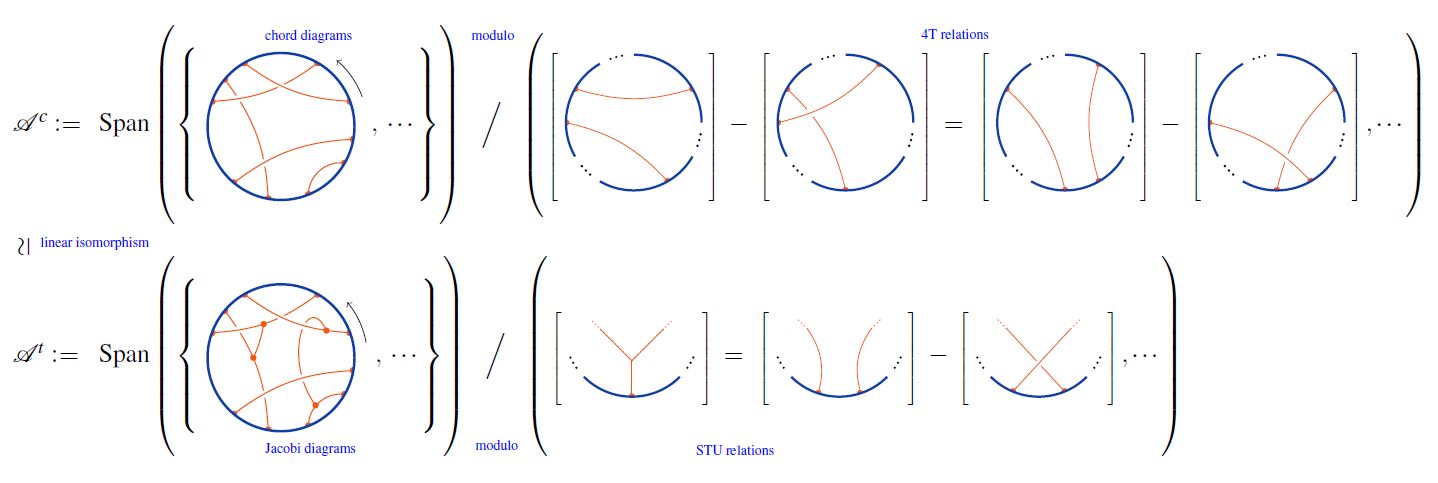

Relation to Jacobi diagrams

chord diagrams modulo 4T are Jacobi diagrams modulo STU:

graphics from Sati-Schreiber 19c

Gauss diagrams of ordinary (virtual) knots

Any knot diagram can be represented faithfully by a certain kind of chord diagram with some extra structure, known as a Gauss diagram (Polyak and Viro 1994).

Recall that classically, a knot is defined as an embedding of the circle into , which can be represented two-dimensionally by projecting onto the plane and marking each double point as either an over-crossing or an under-crossing. One obtains a chord diagram from this knot diagram by considering the original immersing circle and connecting the preimages of each double point by a chord. Then, information about crossings can be represented by orienting the chords from over-crossing to under-crossing, while information about the local writhe of each crossing (in the case of a framed knot) may be encoded by assigning each chord an additional positive or negative sign. Finally, fixing a base point on the original knot gives rise to a Gauss diagram whose underlying chord diagram is naturally rooted.

Once again, this geometric object can be abstracted into a purely combinatorial one, called the Gauss code of the knot (diagram). To construct the Gauss code, begin by assigning arbitrary labels to the crossings, then run the length of the knot (starting at some arbitrary base point) and output the name of each crossing as you visit it, together with a bit (or two bits in the case of a framed knot) specifying whether you are at an over-crossing or an under-crossing (of positive or negative writhe). The underlying (rooted) chord diagram of the knot is thus encoded as a double-occurrence word.

Polyak and Viro called these “Gauss diagrams” after Carl Gauss, who apparently studied the question of which chord diagrams arise from immersions of circles (see the chapter titled “Gauss is back: curves in the plane” of Ghys’s A singular mathematical promenade). This question also played a foundational role in virtual knot theory — indeed, according to Kauffman (1999), the “fundamental combinatorial motivation” for the definition of virtual knots was the idea that it should be possible to interpret an arbitrary Gauss diagram as encoding a knot, now no longer seen as an embedding of into , but into a thickened surface of arbitrary genus.

Chord diagrams of singular knots

By an analogous mechanism, any singular knot with simple double points (i.e., points where the knot intersects itself transversally) gives rise to a chord diagram with chords, by connecting the preimages of these double points. This chord diagram of course does not faithfully represent the original knot (e.g., it does not include any information about over-crossings and under-crossings). However, such chord diagrams nonetheless play an important role in the theory of Vassiliev invariants, by the theorem that the value of a Vassiliev invariant of degree on any singular knot with simple double points depends only on the chord diagram .

Related concepts

| chord diagrams | weight systems |

|---|---|

| linear chord diagrams, round chord diagrams Jacobi diagrams, Sullivan chord diagrams | Lie algebra weight systems, stringy weight system, Rozansky-Witten weight systems |

References

General

Early consideration of round chord diagrams (as “linked diagrams”):

-

Paul R. Stein, On a class of linked diagrams, I. Enumeration, Journal of Combinatorial Theory, Series A Volume 24, Issue 3, May 1978, Pages 357-366 (doi:10.1016/0097-3165(78)90065-1)

-

Paul R. Stein, C. J. Everett, On a class of linked diagrams II. Asymptotics, Discrete Mathematics Volume 21, Issue 3, 1978, Pages 309-318 (doi:10.1016/0012-365X(78)90162-0)

Original discussion of chord diagrams in the context of Vassiliev invariants:

-

Dror Bar-Natan, On the Vassiliev knot invariants, Topology Volume 34, Issue 2, April 1995, Pages 423-472 (doi:10.1016/0040-9383(95)93237-2, pdf)

-

Dror Bar-Natan, Vassiliev and Quantum Invariants of Braids, Geom. Topol. Monogr. 4 (2002) 143-160 (arxiv:q-alg/9607001)

Textbook accounts:

-

Sergei Chmutov, Sergei Duzhin, Jacob Mostovoy, Section 4 of: Introduction to Vassiliev knot invariants, Cambridge University Press, 2012 (arxiv:1103.5628, doi:10.1017/CBO9781139107846)

-

David Jackson, Iain Moffat, Section 11 of: An Introduction to Quantum and Vassiliev Knot Invariants, Springer 2019 (doi:10.1007/978-3-030-05213-3)

Lecture notes:

- Dror Bar-Natan, Alexander Stoimenow, The Fundamental Theorem of Vassiliev Invariants (arXiv:q-alg/9702009)

For chord diagrams and arc diagrams from the perspective of combinatorics, see:

-

Jacques Touchard, Sur un problème de configurations et sur les fractions continues Canadian Journal of Mathematics 4 (1952), 2-25. (doi)

-

Philippe Flajolet and Marc Noy, Analytic combinatorics of chord diagrams, INRIA technical report 3914, March 2000. (pdf)

-

A. Khruzin, Enumeration of chord diagrams arXiv:math/0008209, August 2000. (arxiv)

For the relationship to Gauss diagrams in classical and virtual knot theory, see:

-

Michael Polyak and Oleg Viro, Gauss diagram formulas for Vassiliev invariants, International Mathematics Research Notes 1994:11. pdf

-

Louis Kauffman, Virtual Knot Theory, European Journal of Combinatorics (1999) 20, 663-691. pdf

-

Oleg Viro, Virtual Links, Orientations of Chord Diagrams and Khovanov Homology, Proceedings of 12th Gökova Geometry-Topology Conference, pp. 184–209, 2005. pdf

-

Gauss codes at the Knot Atlas.

For the connection to Vassiliev invariants of singular knots, see:

-

Sergei K. Lando and Alexander K. Zvonkin, Graphs on Surfaces and Their Applications, Springer, 2004. (Chapter 6.)

-

Dror Bar-Natan, On the Vassiliev knot invariants, Topology 34 (1995), 423-472. (html)

-

Simon Willerton, Vassiliev invariants and the Hopf algebra of chord diagrams, Math. Proc. Camb. Phil. Soc. (1996), 119, 55.

-

Greg Muller, “Chord Diagrams and Lie Algebras”, blog post at The Everything Seminar, 25 December 2007.

The following book contains an extensive discussion of chord diagrams associated to singular points of analytic curves:

- Étienne Ghys, A Singular Mathematical Promenade, preliminary version of December 2016. (arXiv:1612.06373) (author pdf)

On Vassiliev invariants of braids via chord diagrams:

- Dror Bar-Natan, Vassiliev and Quantum Invariants of Braids, Geom. Topol. Monogr. 4 (2002) 143-160 (arxiv:q-alg/9607001)

Relation to spherical curves?:

- Noboru Ito, Based chord diagrams of spherical curves (arXiv:2004.12121)

See also:

- Ali Assem Mahmoud, Karen Yeats, Connected Chord Diagrams and the Combinatorics of Asymptotic Expansions (arXiv:2010.06550)

Chord diagrams and weight systems in Physics

The following is a list of references that involve (weight systems on) chord diagrams/Jacobi diagrams in physics:

-

In quantum many body models for for holographic brane/bulk correspondence:

For a unifying perspective (via Hypothesis H) and further pointers, see:

-

Hisham Sati, Urs Schreiber, Differential Cohomotopy implies intersecting brane observables, Adv. Theor. Math. Phys. 26 4 (2022) [arXiv:1912.10425]

-

David Corfield, Hisham Sati, Urs Schreiber: Fundamental weight systems are quantum states Lett. Math. Phys. 113 112 (2023) [arXiv:2105.02871, doi:10.1007/s11005-023-01725-4]

-

Carlo Collari, A note on weight systems which are quantum states, Can. Math. Bull. (2023) arXiv:2210.05399, doi:10.4153/S0008439523000206

Review:

- Carlo Collari, Weight systems which are quantum states, talk at QFT and Cobordism, CQTS (Mar 2023) web, pdf

In Chern-Simons theory

Since weight systems are the associated graded of Vassiliev invariants, and since Vassiliev invariants are knot invariants arising as certain correlators/Feynman amplitudes of Chern-Simons theory in the presence of Wilson lines, there is a close relation between weight systems and quantum Chern-Simons theory.

Historically this is the original application of chord diagrams/Jacobi diagrams and their weight systems, see also at graph complex and Kontsevich integral.

-

Dror Bar-Natan, Perturbative aspects of the Chern-Simons topological quantum field theory, thesis 1991 (spire:323500, proquest:303979053, BarNatanPerturbativeCS91.pdf)

-

Maxim Kontsevich, Vassiliev’s knot invariants, Advances in Soviet Mathematics, Volume 16, Part 2, 1993 (pdf)

-

Daniel Altschuler, Laurent Freidel, Vassiliev knot invariants and Chern-Simons perturbation theory to all orders, Commun. Math. Phys. 187 (1997) 261-287 (arxiv:q-alg/9603010)

-

Alberto Cattaneo, Paolo Cotta-Ramusino, Riccardo Longoni, Configuration spaces and Vassiliev classes in any dimension, Algebr. Geom. Topol. 2 (2002) 949-1000 (arXiv:math/9910139)

-

Alberto Cattaneo, Paolo Cotta-Ramusino, Riccardo Longoni, Algebraic structures on graph cohomology, Journal of Knot Theory and Its Ramifications, Vol. 14, No. 5 (2005) 627-640 (arXiv:math/0307218)

Reviewed in:

- Ismar Volić, Section 4 of: Configuration space integrals and the topology of knot and link spaces, Morfismos, Vol 17, no 2, 2013 (arxiv:1310.7224)

Applied to Gopakumar-Vafa duality:

- Dave Auckly, Sergiy Koshkin, Introduction to the Gopakumar-Vafa Large Duality, Geom. Topol. Monogr. 8 (2006) 195-456 (arXiv:0701568)

See also

-

Marcos Mariño, Chern-Simons theory, matrix integrals, and perturbative three-manifold invariants, Commun. Math. Phys. 253 (2004) 25-49 (arXiv:hep-th/0207096)

-

Stavros Garoufalidis, Marcos Mariño, On Chern-Simons matrix models (pdf, pdf)

For single trace operators in AdS/CFT duality

Interpretation of Lie algebra weight systems on chord diagrams as certain single trace operators, in particular in application to black hole thermodynamics

- Micha Berkooz, Prithvi Narayan, Joan Simón, Section 2.1 of Chord diagrams, exact correlators in spin glasses and black hole bulk reconstruction, JHEP 08 (2018) 192 (arxiv:1806.04380)

In , JT-gravity/SYK-model

Discussion of (Lie algebra-)weight systems on chord diagrams as SYK model single trace operators:

-

Antonio M. García-García, Yiyang Jia, Jacobus J. M. Verbaarschot, Exact moments of the Sachdev-Ye-Kitaev model up to order , JHEP 04 (2018) 146 (arXiv:1801.02696)

-

Yiyang Jia, Jacobus J. M. Verbaarschot, Section 4 of: Large expansion of the moments and free energy of Sachdev-Ye-Kitaev model, and the enumeration of intersection graphs, JHEP 11 (2018) 031 (arXiv:1806.03271)

-

Micha Berkooz, Prithvi Narayan, Joan Simón, Chord diagrams, exact correlators in spin glasses and black hole bulk reconstruction, JHEP 08 (2018) 192 (arxiv:1806.04380)

following:

- László Erdős, Dominik Schröder, Phase Transition in the Density of States of Quantum Spin Glasses, D. Math Phys Anal Geom (2014) 17: 9164 (arXiv:1407.1552)

which in turn follows

- Philippe Flajolet, Marc Noy, Analytic Combinatorics of Chord Diagrams, pages 191–201 in Daniel Krob, Alexander A. Mikhalev,and Alexander V. Mikhalev, (eds.), Formal Power Series and Algebraic Combinatorics, Springer 2000 (doi:10.1007/978-3-662-04166-6_17)

With emphasis on the holographic content:

-

Micha Berkooz, Mikhail Isachenkov, Vladimir Narovlansky, Genis Torrents, Section 5 of: Towards a full solution of the large double-scaled SYK model, JHEP 03 (2019) 079 (arxiv:1811.02584)

-

Vladimir Narovlansky, Slide 23 (of 28) of: Towards a Solution of Large Double-Scaled SYK, 2019 (pdf)

-

Micha Berkooz, Mikhail Isachenkov, Prithvi Narayan, Vladimir Narovlansky, Quantum groups, non-commutative , and chords in the double-scaled SYK model [arXiv:2212.13668]

-

Herman Verlinde, Double-scaled SYK, Chords and de Sitter Gravity [arXiv:2402.00635]

-

Micha Berkooz, Nadav Brukner, Yiyang Jia, Ohad Mamroud, A Path Integral for Chord Diagrams and Chaotic-Integrable Transitions in Double Scaled SYK [arXiv:2403.05980]

and specifically in relation, under AdS2/CFT1, to Jackiw-Teitelboim gravity:

-

Andreas Blommaert, Thomas Mertens, Henri Verschelde, The Schwarzian Theory - A Wilson Line Perspective, JHEP 1812 (2018) 022 (arXiv:1806.07765)

-

Andreas Blommaert, Thomas Mertens, Henri Verschelde, Fine Structure of Jackiw-Teitelboim Quantum Gravity, JHEP 1909 (2019) 066 (arXiv:1812.00918)

-

Henry W. Lin, The bulk Hilbert space of double scaled SYK, J. High Energ. Phys. 2022 60 (2022) arXiv:2208.07032, doi:10.1007/JHEP11(2022)060

-

Henry W. Lin, Douglas Stanford, A symmetry algebra in double-scaled SYK arXiv:2307.15725

In D/D-brane intersections

Discussion of weight systems on chord diagrams as single trace observables for the non-abelian DBI action on the fuzzy funnel/fuzzy sphere non-commutative geometry of Dp-D(p+2)-brane intersections (hence Yang-Mills monopoles):

-

Sanyaje Ramgoolam, Bill Spence, S. Thomas, Section 3.2 of: Resolving brane collapse with corrections in non-Abelian DBI, Nucl. Phys. B703 (2004) 236-276 (arxiv:hep-th/0405256)

-

Simon McNamara, Constantinos Papageorgakis, Sanyaje Ramgoolam, Bill Spence, Appendix A of: Finite effects on the collapse of fuzzy spheres, JHEP 0605:060, 2006 (arxiv:hep-th/0512145)

-

Simon McNamara, Section 4 of: Twistor Inspired Methods in Perturbative FieldTheory and Fuzzy Funnels, 2006 (spire:1351861, pdf, pdf)

-

Constantinos Papageorgakis, p. 161-162 of: On matrix D-brane dynamics and fuzzy spheres, 2006 (pdf)

As codes for holographic entanglement entropy

Chord diagrams encoding Majorana dimer codes and other quantum error correcting codes via tensor networks exhibiting holographic entanglement entropy:

-

Alexander Jahn, Marek Gluza, Fernando Pastawski, Jens Eisert, Majorana dimers and holographic quantum error-correcting code, Phys. Rev. Research 1, 033079 (2019) (arXiv:1905.03268)

-

Han Yan, Geodesic string condensation from symmetric tensor gauge theory: a unifying framework of holographic toy models, Phys. Rev. B 102, 161119 (2020) (arXiv:1911.01007)

For Dyson-Schwinger equations

Discussion of round chord diagrams organizing Dyson-Schwinger equations:

-

Nicolas Marie, Karen Yeats, A chord diagram expansion coming from some Dyson-Schwinger equations, Communications in Number Theory and Physics, 7(2):251291, 2013 (arXiv:1210.5457)

-

Markus Hihn, Karen Yeats, Generalized chord diagram expansions of Dyson-Schwinger equations, Ann. Inst. Henri Poincar Comb. Phys. Interact. 6 no 4:573-605 (arXiv:1602.02550)

-

Paul-Hermann Balduf, Amelia Cantwell, Kurusch Ebrahimi-Fard, Lukas Nabergall, Nicholas Olson-Harris, Karen Yeats, Tubings, chord diagrams, and Dyson-Schwinger equations [arXiv:2302.02019]

Review in:

- Ali Assem Mahmoud, Section 3 of: On the Enumerative Structures in Quantum Field Theory (arXiv:2008.11661)

Last revised on May 28, 2021 at 13:21:28. See the history of this page for a list of all contributions to it.