nLab geometric quantization

Context

Geometric quantization

geometric quantization higher geometric quantization

geometry of physics: Lagrangians and Action functionals + Geometric Quantization

Prerequisites

Prequantum field theory

-

prequantum circle n-bundle = extended Lagrangian

-

prequantum 1-bundle = prequantum circle bundle, regularcontact manifold,prequantum line bundle = lift of symplectic form to differential cohomology

-

Geometric quantization

Applications

Physics

physics, mathematical physics, philosophy of physics

Surveys, textbooks and lecture notes

theory (physics), model (physics)

experiment, measurement, computable physics

-

-

-

Axiomatizations

-

Tools

-

Structural phenomena

-

Types of quantum field thories

-

Symplectic geometry

Background

Basic concepts

Classical mechanics and quantization

Contents

- Idea

- Definition

- Properties

- Functorial dependence on choices

- Compatibility of quantization with symplectic reduction

- Characteristic central extensions

- Examples

- Schrödinger representation

- Kähler manifolds

- The 2-sphere

- Tori

- Theta functions

- Quantization of Chern-Simons theory

- Quantization of loop groups / of the WZW model

- Quantization in Gromov-Witten theory

- Quantization of the bosonic string -model

- Related concepts

- References

Idea

Geometric quantization is one formalization of the notion of quantization of a classical mechanical system/classical field theory to a quantum mechanical system/quantum field theory. In comparison to deformation quantization it focuses on spaces of states, hence on the Schrödinger picture of quantum mechanics.

Ingredients

With a symplectic manifold regarded as a classical mechanical system, geometric quantization produces quantization of this to a quantum mechanical system by

-

realize the symplectic form as the curvature of a -principal bundle with connection (which requires the form to have integral periods): called the prequantum circle bundle;

-

choose a polarization – a splitting of the abstract phase space into “coordinates” and “momenta”;

and then form

-

a Hilbert space of states as the space of sections of the associated line bundle which depend only on the “coordinates” (not on the “momenta”);

-

associate with every function on the symplectic manifold – every Hamiltonian – a linear operator on this Hilbert space.

History and variants

The approach is due to Alexandre Kirillov (“orbit method”), Bertram Kostant and Jean-Marie Souriau. See the References below. It is closely related to Berezin quantization? and the subject of coherent states.

In a long term project Alan Weinstein and many of his students have followed the idea that the true story behind geometric quantization crucially involves symplectic Lie groupoids: higher symplectic geometry. See geometric quantization of symplectic groupoids for more on this.

More generally, there is higher geometric quantization.

Overview

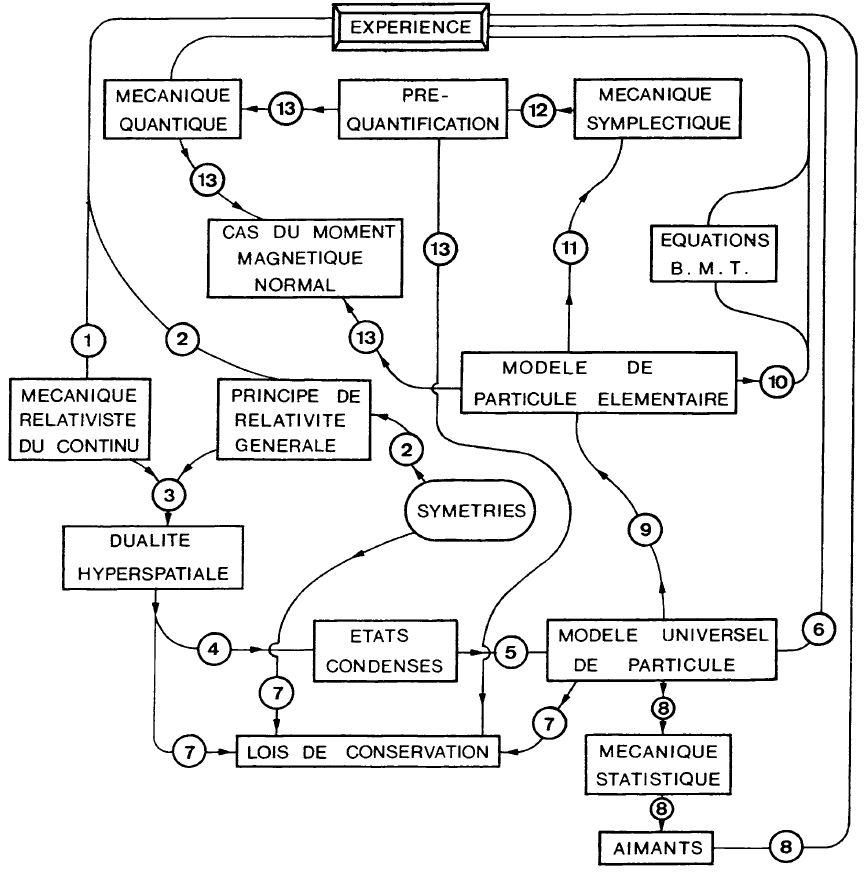

This overview is taken from (Baez).

Geometric quantization is a tool for understanding the relation between classical physics and quantum physics. Here’s a brief sketch of how it goes.

-

We start with a classical phase space: mathematically, this is a manifold with a symplectic structure .

-

Then we do prequantization: this gives us a Hermitian line bundle over , equipped with a connection whose curvature equals . is called the prequantum line bundle.

Warning: we can only do this step if satisfies the Bohr-Sommerfeld condition, which says that defines an integral cohomology class. If this condition holds, and are determined up to isomorphism, but not canonically.

-

The Hilbert space of square-integrable sections of is called the prequantum Hilbert space. This is not yet the Hilbert space of our quantized theory – it’s too big. But it’s a good step in the right direction. In particular, we can prequantize classical observables: there’s a map sending any smooth function on to an operator on . This map takes Poisson brackets to commutators, just as one would hope. The formula for this map involves the connection .

-

To cut down the prequantum Hilbert space, we need to choose a polarization, say . What’s this? Well, for each point , a polarization picks out a certain subspace of the complexified tangent space at . We define the quantum Hilbert space, , to be the space of all square-integrable sections of that give zero when we take their covariant derivative at any point in the direction of any vector in . The quantum Hilbert space is a subspace of the prequantum Hilbert space.

Warning: for to be a polarization, there are some crucial technical conditions we impose on the subspaces . First, they must be isotropic: the complexified symplectic form must vanish on them. Second, they must be Lagrangian: they must be maximal isotropic subspaces. Third, they must vary smoothly with . And fourth, they must be integrable.

-

The easiest sort of polarization to understand is a real polarization. This is where the subspaces come from subspaces of the tangent space by complexification. It boils down to this: a real polarization is an integrable distribution on the classical phase space where each space is Lagrangian subspace of the tangent space .

-

To understand this rigamarole, one must study examples! First, it’s good to understand how good old Schrödinger quantization fits into this framework. Remember, in Schrödinger quantization we take our classical phase space to be the cotangent bundle of a manifold called the classical configuration space. We then let our quantum Hilbert space be the space of all square-integrable functions on .

Modulo some technical trickery, we get this example when we run the above machinery and use a certain god-given real polarization on , namely the one given by the vertical vectors.

-

It’s also good to study the Bargmann–Segal representation, which we get by taking with its god-given symplectic structure (the imaginary part of the inner product) and using the god-given Kähler polarization. When we do this, our quantum Hilbert space consists of analytic functions on which are square-integrable with respect to a Gaussian measure centered at the origin.

-

The next step is to quantize classical observables, turning them into linear operators on the quantum Hilbert space . Unfortunately, we can’t quantize all such observables while still sending Poisson brackets to commutators, as we did at the prequantum level. So at this point things get trickier and my brief outline will stop. Ultimately, the reason for this problem is that quantization is not a functor from the category of symplectic manifolds to the category of Hilbert spaces – but for that one needs to learn a bit about category theory.

Basic Jargon

Here are some definitions of important terms. Unfortunately they are defined using other terms that you might not understand. If you are really mystified, you need to read some books on differential geometry and the math of classical mechanics before proceeding.

-

complexification: We can tensor a real vector space with the complex numbers and get a complex vector space; this process is called complexification. For example, we can complexify the tangent space at some point of a manifold, which amounts to forming the space of complex linear combinations of tangent vectors at that point.

-

distribution: The word “distribution” means many different things in mathematics, but here’s one: a “distribution” on a manifold is a choice of a subspace of each tangent space , where the choice depends smoothly on .

-

Hamiltonian vector field: Given a manifold with a symplectic structure , any smooth function can be thought of as a “Hamiltonian”, meaning physically that we think of it as the energy function and let it give rise to a flow on describing the time evolution of states. Mathematically speaking, this flow is generated by a vector field called the “Hamiltonian vector field” associated to . It is the unique vector field such that

In other words, for any vector field on we have

The vector field is guaranteed to exist by the fact that is nondegenerate.

-

integrable distribution: A distribution of subspaces of the tangent bundle on a smooth manifold is “integrable” if at least locally, there is a foliation of by submanifolds such that is the tangent space of the submanifold containing the point .

-

integral cohomology class: Any closed differential p-form on a smooth manifold defines an element of the th de Rham cohomology of . This is a finite-dimensional vector space, and it contains a lattice called the th integral cohomology group of . We say a cohomology class is integral if it lies in this lattice. Most notably, if you take any connection on any Hermitian line bundle over , its curvature -form will define an integral cohomology class once you divide it by . This cohomology class is called the first Chern class, and it serves to determine the line bundle up to isomorphism.

-

Poisson brackets: Given a symplectic structure on a manifold and given two smooth functions on that manifold, say and , there’s a trick for getting a new smooth function on the manifold, called the Poisson bracket of and .

This trick works as follows: given any smooth function we can take its differential , which is a -form. Then there is a unique vector field , the Hamiltonian vector field associated to , such that

Using this we define

It’s easy to check that we also have . So says how much changes as we differentiate it in the direction of the Hamiltonian vector field generated by .

In the familiar case where is with momentum and position coordinates , , the Poisson brackets of and work out to be

-

square-integrable sections: We can define an inner product on the sections of a Hermitian line bundle over a manifold with a symplectic structure. The symplectic structure defines a volume form which lets us do the necessary integral. A section whose inner product with itself is finite is said to be square-integrable. Such sections form a Hilbert space called the “prequantum Hilbert space”. It is a kind of preliminary version of the Hilbert space we get when we quantize the classical system whose phase space is .

-

symplectic structure: A symplectic structure on a manifold is a closed -form which is nondegenerate in the sense that for any nonzero tangent vector at any point of , there is a tangent vector at that point for which is nonzero.

-

connection: The group is the group of unit complex numbers. Given a complex line bundle with an inner product on each fiber , a connection on is a connection such that parallel translation preserves the inner product.

-

vertical vectors: Given a bundle over a manifold , we say a tangent vector to some point of is vertical if it projects to zero down on .

Definition

Geometric quantization involves two steps

Geometric prequantization

Prequantum line bundle

Given the symplectic form , a prequantum circle bundle for it is a circle bundle with connection whose curvature is .

In other words, prequantization is a lift of through the curvature-exact sequence of ordinary differential cohomology (see there).

The multiple of the Chern class of this line bundle is identified with the inverse Planck constant.

Prequantum states

A prequantum state is a section of the prequantum bundle.

This becomes a quantum state or wavefunction if polarized (…).

Prequantum operators

Let be a prequantum line bundle with connection for . Write for its space of smooth sections, the prequantum space of states.

Definition

For a function on phase space, the corresponding quantum operator is the linear map

given by

where

-

is the Hamiltonian vector field corresponding to ;

-

is the covariant derivative of sections along for the given choice of prequantum connection;

-

is the operation of degreewise multiplication pf sections.

Remark

(origin of the formulas for prequantum operators)+

The formula (1) may look a bit mysterious on first sight. The correction term to the covariant derivative appearing in this formula is ultimately due to the fact that with the Hamiltonian vector field corresponding to a Hamiltonian via

then the Lie derivative of (the symplectic potentiation, related by ) is

for

Here the second term on the right is what yields the covariant derivative in (1), while the first summand is the correction term in (1).

A derivation of these formulas from first principles is given in (Fiorenza-Rogers-Schreiber 13a, example 3.2.3 and remark 3.3.16).

Geometric quantization

Given a prequantum bundle as above, the actual step of genuine geometric quantization consists first of forming half its space of sections in a certain sense. Physically this means passing to the space of wavefunctions that depend only on canonical positions but not on canonical momenta. Second, subgroups of the group of (exponentiated) prequantum operators are made to descend to this space of quantum states, these are the quantum operators or quantum observables.

Quantum states

Historically, the traditional way to formalize the formation of the space of quantum states is as a 3-step process

-

choose a Polarization;

-

choose a Metaplectic correction;

-

form the induced space of quantum states as the space of polarized sections of the prequantum line bundle tensored a certain half-form bundle.

This we discuss at

This traditional route via polarizations and metaplectic corrections has the disadvantage that mathematically it is not a very natural operation. However, under mild conditions it turns out to be equivalent to the following mathematically very natural construction

-

choose a KU-orientation, hence a spin^c structure of compatible with the given prequantum bundle;

-

take the space of quantum states to be the push-forward in complex K-theory of the prequantum line bundle to the point, hence the index of the spin^c Dirac operator twisted by the prequantum line bundle.

This general geometric quantization by push-forward is discussed below at

In the special case that the prequantum line bundle admits a Kähler polarization this push-forward quantization has a direct expression in terms of the complex abelian sheaf cohomology and of the Dolbeault operator of the prequantum holomorphic line bundle. Now the choice of metaplectic correction is precisely a spin structure (a “Theta characteristic”) and the index is now that of the Dolbeault-Dirac operator which is equivalently just the Euler characteristic of the holomorphic abelian sheaf cohomology of the prequantum line bundle. This complex Dolbeault quantization case we discuss in

and

Quantum state space as space of polarized sections

For a symplectic manifold, choose a Kähler polarization, hence an involutive Lagrangian subbundle such that . Choose moreover a metaplectic correction of . This defines the half-density bundle along .

Let now be a prequantum line bundle for .

Definition

The space of quantum states of the prequantum bundle defined by the choice of Kähler polarization and metaplectic correction is the space of sections of the tensor product which are covariant derivative covariantly constant with respect to along and square integrable with respect to the induced integration over :

For instance (Bates-Weinstein, def. 7.17).

Remark

In the case of Kähler polarization it is useful to write for the canonical line bundle of the polarization and for the corresponding choice of metaplectic correction/Theta characteristic.

Quantum state space as Euler characteristic of prequantum sheaf cohomology

Let be a compact topological space symplectic manifold, a prequantum line bundle, a Kähler polarization and a metaplectic correction.

Definition

The corresponding Euler quantum Hilbert space is the virtual vector space

which is the alternating direct sum of the Dolbeault cohomology space of with coefficients in the tensor product of the prequantum line bundle with the metaplectic correction/Theta characteristic.

Remark

The Kodaira vanishing theorem asserts that if is a positive line bundle then all the higher cohomology groups in the above expression vanish. Therefore in this case the definition coincides with that via polarizations in def. above.

Quantum state space as index of Dolbeault-Dirac operator

Suppose again that is equipped with a Kähler polarization.

We need the following general fact on spin structures over Kähler manifolds.

Proposition

A choice of spin structure on the Kähler manifold (of real dimension ) is equivalently a choice of square root (“Theta characteristic”) of the canonical line bundle .

Given such a choice, there is a natural isomorphism between the spinor bundle and the (anti-)holomorphic form bundle tensored by this square root

Finally, the corresponding Dirac operator is the Dolbeault-Dirac operator .

See at spin structure – Over a Kähler manifold.

Remark

It follows that the Dirac operator on which is twisted by the connection on the prequantum holomorphic line bundle is of the form

Observe how from the point of view of just the Dolbeault operator, this is twisting not just by the prequantum line bundle itself but by the metaplectically corrected prequantum line bundle , while from the point of view of the Dirac operator it is just twisting by , since tensoring with the square root line bundle induces the isomorphism between the antiholomorphic differential form bundle and the actual spinor bundle over the Kähler manifold.

Definition

The Dolbeault-Dirac space of quantum states of is the index of the -twisted Dolbeault-Dirac operator (the Todd genus)

Remark

This definition agrees with that by abelian sheaf cohomology in def.

Remark

What before in the quantization prescription by polarization and by abelian sheaf cohomology was the “metaplectic correction” introduced “by hand” is now naturally part of the isomorphism of prop. which identifies the Dirac operator with the Dolbeault-Dirac operator.

Quantum state spaces as index of the -Dirac operator

Finally we come to the true definition of geometric quantization, the most general and at the same time most natural one which contains the above as special cases.

The actual definition is def. below. Here we lead up to it by spelling out the ingredients.

We need the following general facts about spin^c Dirac operators.

Definition

For , the spin^c-Lie group is equivalently

-

the tensor product of the ordinary spin group with the circle group over the group of order 2

-

of the homotopy fiber product of the universal smooth second Stiefel-Whitney class and the mod-2 reduction of the universal first Chern class in smooth infinity-groupoids:

Here the top horizontal map is called the universal determinant line bundle map.

See at spin^c group for more details.

Remark

It follows that if we represent elements of as equivalence classes of pairs , then the determinant line bundle map of def. is given by

where on the right we write the group operation in the abelian group additively.

This factor of 2 on the right is crucial in all of the following.

Definition

Let be an oriented smooth manifold. A smooth spin^c structure on is a lift of the classifying map of its tangent bundle through the left vertical map in def.

Remark

In words this says that a spin^c structure on an oriented manifold is a choice of circle group-principal bundle or equivalenty of hermitian complex line bundle such that its first Chern class modulo 2 equals the second Stiefel-Whitney class of . If this second Stiefel-Whitney class vanishes (as an element in ) this means that has a genuine spin structure. So in other words whenever the determinant line bundle of a spin^c structure (in the sens of def. ) has a first Chern class that is divisible by 2, then there is an actual spin^c structure.

We can formalize this statement as follows: there is a commuting square of the form

similar to the one in def. but crucially different in that here we have just the cartesian product of with in the top left. In the standard presentation of these objects this diagram commutes on the nose (filled by a canonical homotopy) simply because both ways to go from the top left to the bottom right hit : the left-bottom one because is essentially by definition such that the second SW class trivializes on it, and the top-right one because first multiplying by 2 and then reducing mod 2 is 0.

Since the diagram commutes, the universal property of the above homotopy pullback says that there is a canonically induced map

Of course this is just the evident quotient projection which on elements is simply the identity

only that on the right we regard the pair as a placeholder for its equivalence class in the tensor product over .

Moreover, the universal property of the homotopy pullback says that every spin^c structure whose underlying determinant line bundle is such that its first Chern class is divisible by 2 actually factors through this map, hence that it is just the product of an ordinary -principal bundle with a circle bundle.

This is the crucial relation by which the K-theoretic quantization will harmonize with the above Euler- and Dolbeault- quantization, discussed below.

Definition

For an even number, write

for the canonical complex spin representation, which decomposes into two chiral irreducible representations

Then the canonical spin^c-representation

is the one given in the components of remark by

(first act with the spin-component in the usual way and then multiply by ).

As discussed at representation we may think of this as a morphism of smooth groupoids (stacks) of the form

Definition

Given a spin^c structure , def. , the associated spinor bundle is the one modulated by

Crucial for the comparison of the K-theoretic quantization to be defined in a moment and the above Euler/Dolbeault quantization is the following:

Remark

By remark it follows that in the case that the determinant line bundle of the spin^c structure is divisible by 2, hence in the case that , then the -spinor bundle of def. is just the tensor product of the ordinary underlying spinor bundle with half the determinant line bundle:

Let now be a (pre-)symplectic manifold and let be a prequantum line bundle.

Definition

Given a spin^c structure on whose underlying determinant line bundle coincides, up to equivalence, with , then the spin^c quantization of this prequantum data is the index of the corresponding spin^c Dirac operator :

Remark

This is equivalently the push-forward in complex K-theory of the prequantum line bundle to the point.

Moreover, on cocycles this push-forward is expressed by the traditional construction of Hilbert spaces of quantum states:

let be a manifold equipped with a Riemannian metric, a spinor bundle and a Dirac operator . Then the corresponding K-homology cycle is:

-

the Hilbert space of square integrable sections of the spinor bundle;

-

equipped with the action by fiberwise multiplication of the C*-algebra of functions vanishing at infinity

(which is by bounded operators)

-

and equipped with the Dirac operator as the -graded Fredholm operator defining the K-homology class.

Together with is equivalent an element

Postcomposition of K-theory classes with this map is the push-forward/index map in K-theory.

Remark

This definition does not assume any choice of polarization, nor any choice of complex structure etc. On the other hand, every choice of almost complex structure (hence in particular of Kähler polarization) does induce a spin^c structure, as discussed there. See also (Borthwick-Uribe 96).

So then we can compare:

Proposition

If a choice of Kähler polarization exists on the compact prequantum geometry , then the K-theoretic quantization of def. coincides with the Dolbeault-Dirac quantization of def. and hence, by remark , with the Euler-characteristic definition, def. , so that all the respectives spaces of quantum states agree:

This is to some extent discussed for instance in (Hochs 08, lemma 3.32, Paradan 09, prop. 2.2).

Proof

Let be a choice of square root (Theta characteristic) of the canonical line bundle, which according to is a choice of spin structure in the Kähler manifold. Then by that same proposition the corresponding spinor bundle is isomorphic to

and so the corresponding -twisted spinor bundle is

where we have re-bracheted just for emphasis of how the metaplectic correction appears as part of the spinor bundle.

At the same time, by remark we have that under this assumption that an actual spin structure exists, the -spinor bundle is isomorphic to

So the two spinor bundles agree. It is now sufficient to observe that under this identification both the Dolbeault-Dirac operator as well as the spin^c Dirac operator have the same symbol to conclude that they have the same index.

Remark

The assumption in the above that we do have a spin structure is only for comparison with the Euler-/ Dolbeault-quantization. It is not necessary for the K-theoretic geometric quantization by spin^c structure.

In the general case the determinant line bundle of the spin^c structure may not admit a square root. (Its failure of having a square root will be compensated precisely by the failure of there being a genuine spin structure.) Still, by the above discussion the index of the corresponding spin^c structure is like a quantization of a would-be square root of the determinant line bundle in this case.

Quantum operators / observables

Given a Hamiltonian action on the symplectic manifold by a Lie group , we can apply the above K-theoretic quantization by push-foward in -equivariant K-theory, to

This is the representation ring of and hence yields not just a Hilbert space, but a Hilbert space equipped with a -action. This is the action by quantum operators, quantizing the -actions. Generalized orientation theory gives the necessary condition for this quantization to exist: needs to be oriented not just in K-theory (spin^c structure) but in -equivariant K-theory (equivariant spin^c structure).

So the geometric quantization of observables is essentially what mathematically is known as Dirac induction.

Properties

Functorial dependence on choices

-

L. Charles, Semi-classical properties of geometric quantization with metaplectic correction (arXiv:math/0602168)

Chapter 3 of

- Lauridsen, Aspects of quantum mathematics – Hitchin connections and the AJ conjecture, PhD thesis Aarhus 2010 (pdf)

Compatibility of quantization with symplectic reduction

On the relation between geometric quantization and symplectic reduction:

Characteristic central extensions

To a large extent geometric quantization is realized by central extension of various Lie groups arising in classical mechanics/symplectic geometry.

higher and integrated Kostant-Souriau extensions:

(∞-group extension of ∞-group of bisections of higher Atiyah groupoid for -principal ∞-connection)

(extension are listed for sufficiently connected )

Examples

Schrödinger representation

We discuss how the standard Schrödinger representation of the canonical commutation relation arises via geometric quantization:

Consider the Cartesian space with canonical coordinate functions denoted and to be called the canonical coordinate and its canonical momentum and equipped with the constant differential 2-form given in in (?) by

This is closed in that , and invertible in that the contraction of tangent vector fields into it (def. ) is an isomorphism to differential 1-forms, and as such it is a symplectic form.

A choice of presymplectic potential for this symplectic form is

in that . (Other choices are possible, notably ).

For

a smooth function (an observable), we say that a Hamiltonian vector field for it (as in def. ) is a tangent vector field whose contraction into the symplectic form (2) is the de Rham differential of :

Consider the foliation of this phase space by constant--slices

These are also called the leaves of a real polarization of the phase space.

(Other choices of polarization are possible, notably the constant -slices.)

We says that a smooth function

is polarized if its covariant derivative with connection on a bundle along the leaves vanishes; which for the choice of polarization in (5) means that

which in turn, for the choice of presymplectic potential in (3), means that

The solutions to this differential equation are of the form

for any smooth function, now called a wave function.

This establishes a linear isomorphism between polarized smooth functions and wave functions.

By (4) we have the Hamiltonian vector fields

The corresponding Poisson bracket is

The action of the corresponding quantum operators and on the polarized functions (6) is as follows

and

Hence under the identification (6) we have

This is called the Schrödinger representation of the canonical commutation relation (7).

Kähler manifolds

If the symplectic manifold happens to be also a Kähler manifold there are natural choices of prequantization:

-

the prequantum line bundle is a holomorphic line bundle since its curvature is ;

-

a polarization is given by the anti-holomorphic tangent bundle ;

-

a polarized section is a holomorphic section;

-

the dimension of the space of states (in geometric quantization) is given by the Riemann-Roch theorem, see (Hitchin).

Applied to a symplectic vector space this yields the Bargmann-Fock representation? of the Heisenberg group.

The 2-sphere

Consider the 2-sphere with its canonical round volume form as a symplectic manifold. This admits a complex structure such that the subgroup of the diffeomorphism group which preserves is the special orthogonal group . The corresponding Kähler metric is a multiple of the standard round Riemannian metric on the 2-sphere.

By the identification the prequantum bundles on are classified by .

The Hilbert space is

the space of holomorphic sections of such a holomorphic line bundle. The universal cover of naturally acts on this Hilbert space. The canonical coordinate functions naturally act on and as such form a Lie algebra representation of the special orthogonal Lie algebra.

A way to reduce the number of choices in this example of geometric quantization is to proceed by quantization via the A-model, see (Gukov-Witten 08, p. 6 onwards).

For more see geometric quantization of the 2-sphere.

Tori

- G. G. Athanasiu, E. G. Floratos, Stam Nicolis, Holomorphic Quantization on the Torus and Finite Quantum Mechanics (arXiv:hep-th/9509098)

Theta functions

See at theta function.

Quantization of Chern-Simons theory

The geometric quantization of Chern-Simons theory leads to invariants for 3-manifolds.(Witten 89).

See at quantization of Chern-Simons theory for more.

Quantization of loop groups / of the WZW model

See at quantization of loop groups.

Quantization in Gromov-Witten theory

Geometric quantization appears in Gromov-Witten theory. See (Clader-Priddis-Shoemaker 13).

Quantization of the bosonic string -model

For discussion of the geometric quantization of the bosonic string 2d sigma-model see at string – Symplectic geometry and geometric quantization .

Related concepts

duality between algebra and geometry

in physics:

partition functions in quantum field theory as indices/genera/orientations in generalized cohomology theory:

References

General

Original references include

-

Jean-Marie Souriau, Structure des systemes dynamiques, Dunod, Paris (1970)

Translated and reprinted as (see section V.18 for geometric quantization):

Jean-Marie Souriau, Structure of dynamical systems - A symplectic view of physics, Brikhäuser (1997) (doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-0281-3)

-

Bertram Kostant, Quantization and unitary representations, in Lectures in modern analysis and applications III, Lecture Notes in Math. 170 (1970), Springer Verlag, 87—208

-

Jean-Marie Souriau, Modèle de particule à spin dans le champ électromagnétique et gravitationnel, Annales de l’I.H.P. Physique théorique, 20 no. 4 (1974), p. 315-364 (numdam)

-

Bertram Kostant, On the definition of quantization, in Géométrie Symplectique et Physique Mathématique, Colloques Intern. CNRS, vol. 237,

Paris (1975) 187—210

-

Victor Guillemin, Shlomo Sternberg, Geometric Asymptotics, Math. Surveys no. 14, Amer. Math. Soc. (1977) (web)

-

Alexandre Kirillov, Geometric quantization Dynamical systems – 4, Itogi Nauki i Tekhniki. Ser. Sovrem. Probl. Mat. Fund. Napr., 4, VINITI, Moscow, 1985, 141–176 (web)

A fairly comprehensive textbook with modern developments is

- Nicholas Woodhouse, Geometric Quantization, Oxford University Press (1997)

Introductions and lecture notes include

-

William Gordon Ritter, Geometric Quantization (arXiv:math-ph/0208008)

-

Matthias Blau, Symplectic geometry and geometric quantization (pdf)

- Eugene Lerman, Geometric quantization; a crash course (arXiv:1206.2334)

Lecture notes with an emphasis on semiclassical states:

- Sean Bates, Alan Weinstein, Lectures on the geometry of quantization, AMS (1997) [pdf]

A careful discussion of the polarization-step from prequantization to quantization is in

-

Jędrzej Śniatycki, Wave functions relative to a real polarization, Internat. J. Theoret. Phys., 14 4 (1975) 277-288 [doi:10.1007/BF01807689)]

-

Jędrzej Śniatycki, Geometric Quantization and Quantum Mechanics, Applied Mathematical Sciences 30, Springer-Verlag (1980) [doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-6066-0]

-

Jędrzej Śniatycki, Lectures on Geometric Quantization, in Geom. Integrability & Quantization (2016) 95-129 [doi:10.7546/giq-17-2016-95-129]

The special case of Kähler quantization is discussed for instance in

- Nigel Hitchin, Flat connections and geometric quantization, Comm. Math. Phys. 131 (1990), no. 2, 347–380.

and for almost Kähler structure in

- David Borthwick, Alejandro Uribe, Almost complex structures and geometric quantization (arXiv:dg-ga/9608006)

Discussion with an emphasis of quantizing classical field theory on curved spacetime is in

- Nicholas Woodhouse, Geometric quantization and quantum field theory in curved space-times, Reports on Mathematical Physics 12:1, (1977) 45–56

(For more on geometric quantization of quantum field theories see also at Quantization of multisymplectic geometry.)

Aspects at least of geometric prequantization are usefully discussed also in section II of

- Jean-Luc Brylinski, Loop spaces, characteristic classes and geometric quantization, Birkhäuser (1993) (doi:10.1007/978-0-8176-4731-5)

Further reviews include

-

A. Echeverria-Enriquez, M.C. Munoz-Lecanda, N. Roman-Roy, C. Victoria-Monge, Mathematical Foundations of Geometric Quantization Extracta Math. 13 (1998) 135-238 (arXiv:math-ph/9904008)

-

Nima Moshayedi, Notes on Geometric Quantization (arXiv:2010.15419)

The above “Overview” and “Basic Jargon” sections are taken from

Some useful talk notes include

- Eva Miranda, From action-angle coordinates to geometric quantization and back (2011) (pdf)

Discussion with an eye towards the philosophy of physics is in

- Gabriel Catren, Towards a Group-Theoretical Interpretation of Mechanics (PhilSci Archive)

On geometric quantization of the scalar field:

- José Luis Alonso, Carlos Bouthelier-Madre, Jesús Clemente-Gallardo, David Martínez-Crespo, Geometric flavours of Quantum Field theory on a Cauchy hypersurface. Part II: Methods of quantization and evolution [arXiv:2402.07953]

Holographic quantization

The geometric quantization via the A-model is discussed in

- Sergei Gukov, Edward Witten, Branes and Quantization, Adv. Theor. Math. Phys. 13 (2009) 1–73, (arXiv:0809.0305, euclid)

See also the geometric quantization of symplectic groupoids below, around (Hawkins).

-Quantization

- Peter Hochs, Quantisation commutes with reduction for cocompact Hamiltonian group actions 2008 (pdf)

- Paul-Emile Paradan, Spin-quantization commutes with reduction, J. Symplectic Geom. Volume 10, Number 3 (2012), 389-422. (arXiv:0911.1067, Euclid)

See the references at geometric quantization by push-forward.

Examples

The basic example of geometric quantization of a symplectic vector space is discussed in pretty much every text on the matter for instance Nohara, starting with example 2.6.

Discussion of geometric quantization of Chern-Simons theory is for instance in

- Edward Witten (lecture notes by Lisa Jeffrey), New results in Chern-Simons theory, pages 81 onwards in: S. Donaldson, C. Thomas (eds.) Geometry of low dimensional manifolds 2: Symplectic manifolds and Jones-Witten theory (1989) (pdf)

- Scott Axelrod, Steve Della Pietra, and Edward Witten, Geometric quantization of Chern-Simons gauge theory, J. Differential Geom. Volume 33, Number 3 (1991), 787-902. (EUCLID)

Discussion of geometric quantization of abelian varieties, toric varieties, flag varieties and its relation to theta functions is in

- Yuichi Nohara, Independence of polarization in geometric quantization (pdf)

- Andrei Tyurin, Quantization, classical and quantum field theory and theta functions (arXiv:math/0210466v1)

- N.J. Hitchin, Flat connections and geometric quantization, Comm. Math. Phys. 131, n 2 (1990), 347-380, euclid

An appearance of geometric quantization in mirror symmetry is pointed out in

- Andrei Tyurin, Geometric quantization and mirror symmetry, (math.AG/9902027)

For discussion of the geometric quantization of the bosonic string 2d sigma-model see at string – Symplectic geometry and geometric quantization.

Discussion of geometric quantization of self-dual higher gauge theory is in

- Samuel Monnier, Geometric quantization and the metric dependence of the self-dual field theory (arXiv:1011.5890)

Discussion in the context of Gromov-Witten theory:

- Emily Clader, Nathan Priddis, Mark Shoemaker, Geometric Quantization with Applications to Gromov-Witten Theory (arXiv:1309.1150)

Relation to deformation quantization

Discussion of the relation of geometric quantization to deformation quantization is in

- Eli Hawkins, The Correspondence between Geometric Quantization and Formal Deformation Quantization (arXiv:math/9811049)

based on

- Eli Hawkins, Geometric Quantization of Vector Bundles (arXiv:math/9808116)

See also

- Christoph Nölle, Geometric and deformation quantization (arXiv:0903.5336)

For a basic comparative review of both see also section 1 of

- Sergei Gukov, Edward Witten, Branes and Quantization, Adv. Theor. Math. Phys. 13 (2009) 1–73, (arXiv:0809.0305, euclid)

(which then develops geometric quantization via the A-model).

Relation to path integral quantization

Relation to path integral quantization is discussed in

- Laurent Charles, Feynman path integral and Toeplitz Quantization (pdf)

Geometric BRST quantization

The Lie algebroid version of an action groupoid is given (dually) by a BRST complex. Quantization over a BRST complex is hence quantization over an infinitesimal action groupoid. (See at higher geometric quantization).

Geometric quantization over BRST complexes is discussed in the following articles.

-

Takashi Kimura, BRST Quantization and Poisson Reduction, PhD Thesis (1990) (web)

-

José Figueroa-O'Farrill, Takashi Kimura, Geometric BRST quantization (pdf)

Geometric BRST quantization. I. Prequantization, Comm. Math. Phys. Volume 136, Number 2 (1991), 209-229. (Euclid)

-

Gijs Tuynman, Geometric quantization of the BRST charge Comm. Math. Phys. Volume 150, Number 2 (1992), 237-265. (Euclid, pdf)

-

Ronald Fulp, BRST Extension of Geometric Quantization, Foundations of Physics Volume 37, Number 1 (2007), (arXiv:math/0604270)

Supergeometric version

One can consider geometric quantization in supergeometry.

-

S.-M. Fei, H. -Y. Guo und Y. Yu, Symplectic geometry and geometric quantization on supermanifold with numbers, Z. Phys, C - Particles and Fields 45, 339-344 (1989)

-

Gijs M. Tuynman, Super Symplectic Geometry and Prequantization (2003) (arXiv:math-ph/0306049)

Of presymplectic manifolds

Discussion of quantization of presymplectic manifolds is in

-

C. Günther, Presymplectic manifolds and the quantization of relativistic particles, Salamanca 1979, Proceedings, Differential Geometrical Methods In Mathematical Physics, 383-400 (1979)

-

Izu Vaisman, Geometric quantization on presymplectic manifolds, Monatshefte für Mathematik, vol. 96, no. 4, pp. 293-310, 1983

-

Ana Canas da Silva, Yael Karshon, Susan Tolman, Quantization of Presymplectic Manifolds and Circle Actions (arXiv:dg-ga/9705008)

Of generalized complex manifolds

Discussion in generalized complex geometry is in

-

Alan Weinstein, Marco Zambon, Variations on Prequantization (arXiv:math/0412502)

-

Alexander Cardona, Geometric quantization of generalized complex manifolds (pdf)

In higher differential geometry

Geometric quantization in or with tools of higher differential geometry, notably with/over Lie groupoids is discussed in the following references.

- Rogier Bos, Groupoids in geometric quantization PhD Thesis (2007) pdf

The geometric quantization of symplectic groupoids is accomplished in

-

Eli Hawkins, A groupoid approach to quantization, J. Symplectic Geom.. 6:61–125, arXiv:math.SG/0612363

-

Joost Nuiten, section 5.2.2 of Cohomological quantization of local boundary prequantum field theory, MSc thesis, August 2013

Discussion of geometric prequantization in fully fledged higher geometry is in

-

Domenico Fiorenza, Chris Rogers, Urs Schreiber, Higher U(1)-gerbe connections in geometric prequantization, Reviews in Mathematical Physics, Volume 28, Issue 06, July 2016 (arXiv:1304.0236)

-

Domenico Fiorenza, Chris Rogers, Urs Schreiber L-∞ algebras of local observables from higher prequantum bundles, Homology, Homotopy and Applications, Volume 16 (2014) Number 2, p. 107 142 (arXiv:1304.6292)

Last revised on February 14, 2024 at 04:26:20. See the history of this page for a list of all contributions to it.